Highlights from the Kitchen Table Conversation – Beyond the Plate: Rethinking Food Design as a Multisensory, Political, and Participatory Practice

In a world where food systems are increasingly fractured, unsustainable, and inequitable, a new design discipline is emerging—not to fix everything, but to ask better questions. This was the central theme of a recent Kitchen Table Conversation, where our panel of designers, educators, and researchers gathered to explore the evolving field of food design.

What Is Food Design?

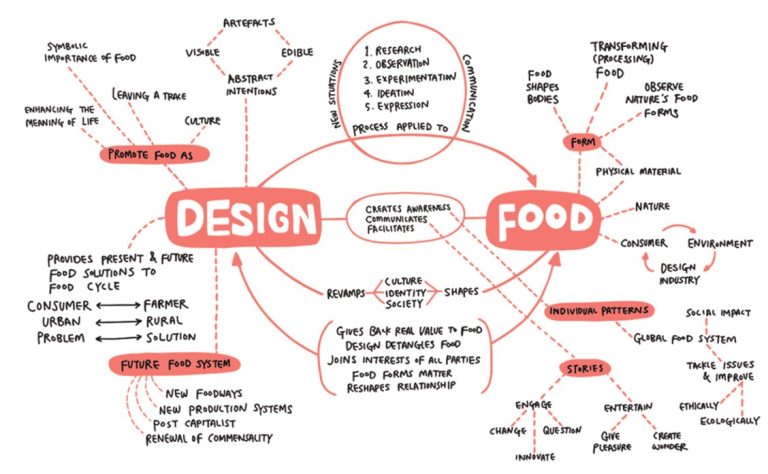

Food design defies easy definition. It’s not just about plating or packaging. As Sophie Lovell put it, it’s about “shifting human attitudes from conquerors to custodians.” It’s a way of thinking that treats food not merely as a consumable, but as a material, medium, and message.

Sonia Massari, a pioneer in sustainable food design, challenged the need for a strict definition altogether. “Do we really need a definition,” she asked, “or do we need to better understand what design can do in the food system?”

From Object to System

Historically, design focused on objects—products, graphics, environments. But as Fabio Parasecoli explained, design has evolved to address services, processes, and systems. This shift coincided with a growing awareness of food’s cultural, political, and environmental dimensions.

Food design, then, is not just about what’s on the plate. It’s about where it comes from, who eats it, and what it means. It’s about systems thinking—understanding how every bite connects to broader networks of production, consumption, and identity.

The Power of the Sense

Leila Snevele, a sensory food designer, reminded us that food is inherently multisensory. “The more senses are involved,” she said, “the more memorable the story becomes.” Her work explores how taste, smell, sound, and touch can be used to enhance perception and provoke reflection.

This sensory richness is not just aesthetic—it’s political. As Priya Mani noted, food is ephemeral, but food systems are not. They leave behind carbon footprints, cultural residues, and ethical dilemmas. Designing with the senses means designing with care.

Design as Dialogue

A recurring theme was the role of the designer—not as a hero, but as a facilitator. Food design is increasingly about co-design, empathy, and participatory processes. It’s about creating spaces where farmers, chefs, policymakers, and communities can collaborate.

As Sonia put it, “Creativity is not an individual action. It’s a collective one.” And that collective action must be grounded in cultural knowledge, social justice, and sustainability.

Technology, Speculation, and the Future

From gastrophysics to digital seasoning, the panel also explored how technology is reshaping food design. Leila’s speculative work imagines futures where we season food with visuals or design dining rituals for interspecies tables.

But even in these futuristic visions, the core remains the same: food design is about connection—to each other, to the planet, and to the systems that sustain us.

Conclusion: Toward a More Relational Future

Orlando Lovell summed up: ‘Food design is still a young field, but it’s growing fast—and growing deep. It’s not just about making things; it’s about making meaning. It’s about asking: What if we designed food systems with empathy? What if we treated food as a language, a bridge, a commonality?’

At the end of our meetup, one thing was clear: food design is not a trend. It’s a transformative practice—one that invites us all to the table to help change the conversation about food.

By David Matchett

Illustration : The Food & Design Manifesto is an initiative of the Dutch Institute of Food & Design (DIFD), founded by eating designer Marije Vogelzang, in collaboration with What Design Can Do.