Overview & report

Questions debated during the 2009 Symposium on Food and Language included whether the preparation, serving, and consumption of food act as a coded language between host and guest, indicating love, affection or even disrespect; revealed power and social status; and asserted nationality and religion.

Simon Schama delivered our Saturday morning keynote address under the title, ‘Mouthing Off: Reflections on Eating and Uttering’, reminding the audience that restaurant critics are seldom cooks and questioning whether we can adequately write about food, likening it to both music and sex, both of which have an extensive literature.

View a PDF programme of events and list of plenary and parallel sessions.

Symposiast Len Fisher, drawing on the philosopher Thomas Nagel’s notion that subjective experiences are unique to each of us, emphasized that scientifically each individual tastes the same shared meal differently. Food writers, then, can either describe the internal experience of the writer or communicate an expectation to the reader, an approach Fisher favors. The language used on a menu can influence the diner’s perception of flavor: when Heston Blumenthal changed the name of The Fat Duck’s ‘Crab Flavored Ice-cream’ to ‘Frozen Crab Bisque’, customers found that it tasted different, less sweet, although the recipe remained exactly the same.

The power of language applies equally to wine. Patrick Baude’s paper, ‘The Hermeneutics of Wine Criticism’, argued that wine critics do not write about wine as such but rather write about the good life to which wine may be a tool. Yet while many of the “descriptors” used in wine-tasting – ‘tarry,’ ‘gooseberries,’ ‘vanilla’, ‘yeasty,’ and even ‘bananas’ and ‘bubblegum’, often seem metaphorical, flowery, or imprecise to the reader or listener, they are often appropriate to the chemical compounds actually present in the wine.

Kimiko Barber addressed whether specific cuisines can be adequately translated into other languages, suggesting that Japanese food is different than western food and therefore its food experiences and sensations are best described in its own language. Barber notes that the Japanese language contains more onomatopoeic and mimetic words, especially food-related words, than English. Elizabeth Andoh, following a similar theme, suggested that in their literal translations some Japanese menus could be mistaken for poetry even while conveying specific information about the food.

The plenary panel discussing “Food and the Book” included Jill Norman (Elizabeth David, Penguin), Judith Jones (Julia Child, Knopf), Susan Friedland (HarperCollins) and cookbook historian Barbara Ketchum Wheaton highlighted the disappearing role of copy editors, recipe testers, and proof-readers among some publishing houses.

Darra Goldstein, defining language in a wider sense, made the case for visual communication by starting her presentation of food in pictures and photographs with an image that, to an astronomer would represent the moon; to a mathematician would represent an ellipse; but that the food-centred audience clearly interpreted as an egg. The debate of food and art, however, remains unresolved.

Other highlights included David Sutton comparing the coarse Anglo-Saxon origins of the words cow, sheep, pig, and oxtail to the refined Norman origins of beef, mutton, and pork; Aylin Öney Tan suggesting that traces of the Sephardic Jewish influences still remain in Turkish cuisine; Birgit Ricquier and Koen Bostoen, referencing their work on the culinary traditions of early Bantu speech communities in Central and Southern Africa, arguing that linguistics can shed light on otherwise hidden stages of human history; Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire championing the wider use of oral history among culinary historians to gather and preserve the memories and life experiences of chefs, waiters, restaurateurs, and diners;

Rachel Laudan proposing an inventory of cuisines, past as well as present, similar to linguisitc inventories; Paul Freedman discussing the changing use of French in mid-19th-century American restaurant menus; and Cathy Kaufman discussing the differences between copyright and patents by tracing various legal cases in which copyright for certain dishes were unsuccessfully sought.

The OSFC warmly thanks the sponsors featured below. We are very grateful for their generosity.

Parallel Sessions

Keynotes

Simon Schama

Darra Goldstein, David Sutton, Tim Wharton

Susan Friedland, Judith Jones, Jill Norman, Barbara Wheaton

Awardees

OFS Young Chefs

Ioannis Hodges-Mameletzis, Ben Keeley, Nicholas Fitzgerald, Grace O’Sullivan, Dan Penn

Cherwell Prize

Willa Zhen

Meals

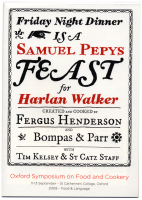

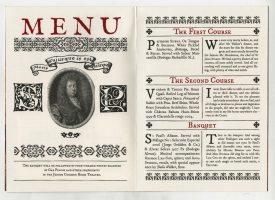

Friday Dinner

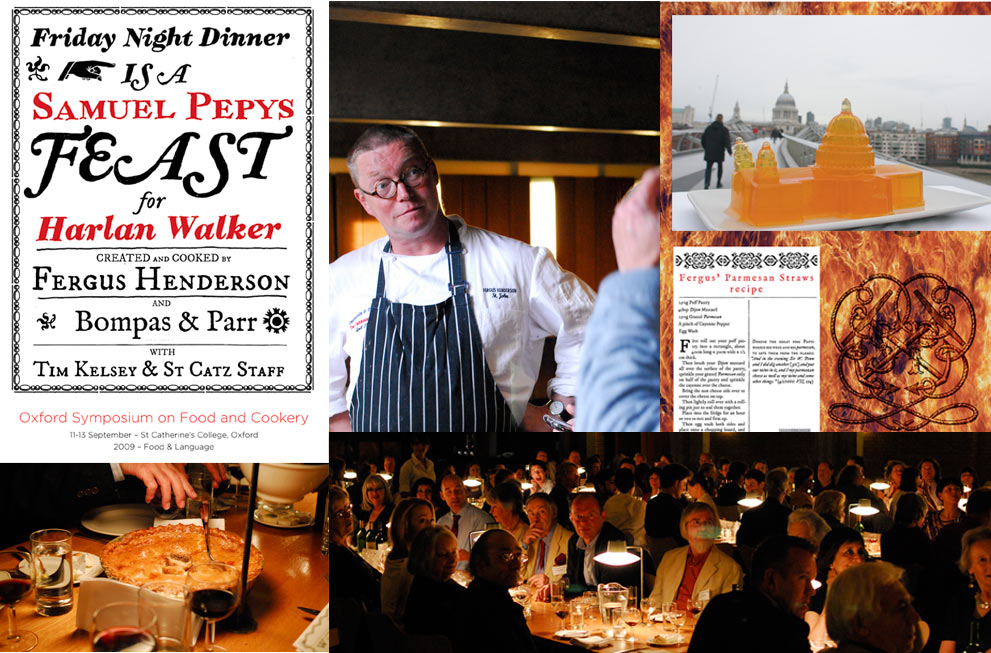

A Samuel Pepys Feast for Harlan Walker

Organised by – Jane Levi

Cooked by – Fergus Henderson & St John Restaurant, Tim Kelsey and the team at St Catz.

Sponsored by – Château Bahans Haut-Brion 1999. Clarendelle rouge 2004. H.R.H. Prince Robert of Luxembourg & Domaine Clarence Dillon. Fayregame, The Fish Society, Wines from Spain, Bompas & Parr, Foods from Spain.

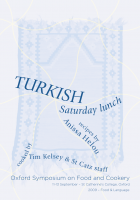

Saturday Lunch

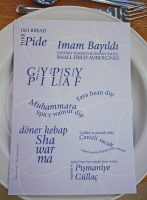

A Turkish Lunch

Organised by – Anissa Helou

Cooked by – Recipes by Anissa Helou. Cooked by Tim Kelsey and the team at St Catz

Sponsored by – Aylin Öney Tan

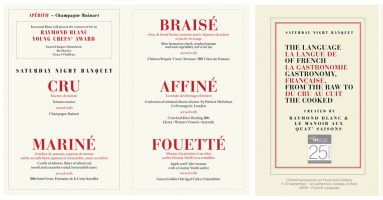

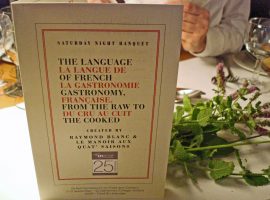

Saturday Dinner

The Language of French Gastronomy, From the Raw to the Cooked

Organised by – Paul Levy

Cooked by – Raymond Blanc and the team at Le Manoir aux Quat’Saisons

Sponsored by – Raymond Blanc and the team at Le Manoir aux Quat’Saisons for designing and preparing our meal and for donating cuttings from the Manoir’s gardens. Max Barber, Cathy Kaufman, Ben Keeley, Grace O’Sullivan and Daniel Penn for helping the prep team at Le Manoir. Ruinart for generously donating their champagne. O. W. Loeb, as well as to Domaine de la Croix Senaillet and Château Pesquié for the wines. Patricia Michelson and La Fromagerie for the French cheeses, especially selected as a tribute to Raymond Blanc. Wychwood Brewery for Green Goblin Oak Aged English Cider (brewed in Oxfordshire). Imperial Caviar UK, M Newitt & Sons and Mash Purveyors, Ltd. for generous reductions on caviar, ox cheek and fruit & vegetables, respectively.

Sunday Lunch

Brazilian Caipirinhas Buffet

Organised by – Marcia Zoladz

Cooked by – Recipes by Marcia Zoladz. Cooked by Tim Kelsey and the team at St Catz

Sponsored by – Aylin Öney Tan, Abelha, Palma Louca Pils, Xingu Black Beer