Garden Seeds in Early Modern England

‘…Such as are old and withered, or else… such as are stark naught’ – Symposiast Malcolm Thick on the variable quality of garden seeds in early Modern England

Without seeds it is impossible to grow most vegetables and, as bread is made from ground seeds, that too would not exist without them. Seeds are therefore the starting point of most gardening and I hope to discuss imports of new types of vegetable seed at the 2018 Symposium. Meanwhile, many of you will be familiar with the biblical parable of the sower in Matthew 13:

3 And he spake many things unto them in parables, saying, Behold, a sower went forth to sow;

4 And when he sowed, some seeds fell by the way side, and the fowls came and devoured them up:

5 Some fell upon stony places, where they had not much earth: and forthwith they sprung up, because they had no deepness of earth:

6 And when the sun was up, they were scorched; and because they had no root, they withered away.

7 And some fell among thorns; and the thorns sprung up, and choked them:

8 But other fell into good ground, and brought forth fruit, some an hundredfold, some sixtyfold, some thirtyfold.

I’m sure many churchgoing gardeners over the centuries have sat in their pews listening to this passage and thought ruefully that Christ made an unrealistic assumption when he spoke this parable- he assumed that the sower had viable seed in the first place. Had He acquired it from an unscrupulous or unskilled seed seller He may well have found that no plants sprang up from any of the grounds they landed on. The problem of seed quality is ever present for gardeners. A parliamentary report in 2013 commented:

Plant reproductive material in the form of seeds and other types of material (such as young plants) is an important first step in the agri-food chain, with farmers, growers, forestry managers and gardeners needing assurance as to the identity of this material in terms of yield and disease resistance, and its quality (for example, purity and germination rate).’

The report went on:

…the EU has over the last 50 years built up a body of legislation, comprising 12 Directives and some 90 supplementary acts, to provide these assurances.

Prior to the EU, the British Parliament passed the Seeds Act 1920 which, in the case of garden seeds, laid down that the seeds were to be tested for purity and germination rates before they were advertised for sale and they should comply with minimum germination rates. Even so, these were not particularly high for some varieties, ranging from 75% for broad beans to 45% for parsnips.

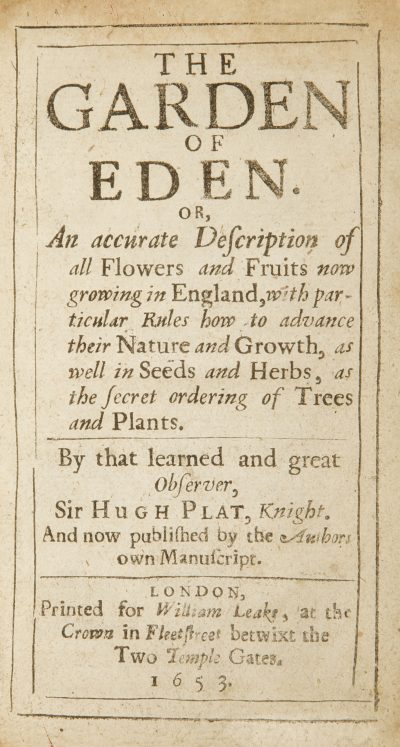

The main problem in the past was that there was no way of telling from merely looking at seeds, whether they would germinate or not. Added to this was the similarity of many seeds- a great many were small, round, and dark in colour- confusing for the inexperienced gardener. In sixteenth century London seeds were often sold by women in the streets, either home-grown or bought from importing merchants. The blame for bad seed was, by the Elizabethan gentleman gardener Sir Hugh Plat, placed squarely on to sellers. In his book on gardening he let his feelings known in a fine stream of invective which gathered pace as he wrote it, eventually taking in the conduct of (women) fowl-sellers as well:

[it] is the ordinary practice in these days, with all such as follow that way, either to deliver the seeds they sell mingled with such as are old and withered, or else without any mingling at all to sell such as are stark naught. I would there were some fit punishment devised for these petit cozeners, by whose means many poor men in England, do oftentimes lose, not only the charge of their seed, but the whole use and benefit of their ground, after they have bestowed the best part of their wealth upon it. Cheapside is as full of these lying and forswearing Huswives as the Shambles and Gracechurch street are of that shameless crew of Poulterers wives, who both daily & most damnably; yea upon the Sabbath day itself, run headlong into willful perjury, almost in every bargain which they make……maintaining their sales, with such bold countenances, and cutting speeches, with such knavish practices, and such forlorn Consciences, as they have both driven honest Matrons from their stalls, and so corrupted a number of young Maiden Servants with their bold and lewd lying, with their desperate swearing and forswearing, that they have made all plain and modest speech, yea all kind of Christianity to seem base and rustical unto them. I would inveigh more bitterly against this sin, if my text would bear it; but now I will leave it unto the several Preachers of the Parishes where they dwel, who can present this matter more sharply, and with less offence than I may; I pray God that either by them, or by the Magistrates, or by one means or other, this great dishonour of God and of Religion may be speedily removed amongst us.

Plat was not alone in condemnation of seed-sellers nor in high flights of invective. Richard Gardiner, a cloth merchant and gardener from Shrewsbury in 1599 held similar views:

I desire that all which would sow onion or others aforesaid in gardens, to provide seedes

of their own growing & not be decieved yearly as commonly they be, to no small

losse in generall to this Land, by those which bee common sellers of Garden seedes,

I cannot omitte nor spare to deliver my minde, concerning the great and abominable

falsehoode of those sortes of people which sell garden seedes:

He goes on to estimate the loss in crops saying

consider how many thousands of pounds are robbed yeerely from the common wealth by these Catterpillars

and he asks that

Almighty God turne their hearts or confound such false proceedings against the commonwealth

The seed-trade was, until the nineteenth century, concentrated in London, one reason for this being the high proportion of seeds imported from abroad – many came from Italy and other Mediterranean countries. The early eighteenth century seedsman Stephen Switzer sought to shift the blame for bad seed on to the foreign producers (and Catholicism). He explained that broccoli seed had to be imported, it was:

a Kind of Italian Kele, or Colewort, which grows on the Sea-Coasts about Naples, and other Places in Italy; from whence the best Seed is yearly exported, that which is saved in England being little worth.

But:

The greatest Difficulty that attends this Affair in the getting Seeds from abroad, is, the great Cheat that those People, who gather it on the Sea-side, put upon the Merchants and consequently upon us here, has been a great Hindrance to using it for this Year: For though I saw the Bag just brought from the Water-side and mark’d with an Italian Mark and Character, and saw the Bill of Parcels, &c in the Importer’s own Hands, yet when it came up, it was nothing else but Turneps; so little Faith is to be found amongst those Collectors of Seeds, who no doubt think it no Sin to cheat Hereticks.

Switzer proposed to sow some seed in his own nursery- ground before selling to his customers, to check on its germination rate and the quality.

The nineteenth century was plagued by growing mass production of food and accompanying adulteration. Adulteration was also a problem for buyers of seeds and the Adulteration of Seeds Act, 1869 sought to alleviate this. But it only covered the sale of seed known to be dead and artificially coloured seed. The Country Gentleman’s Magazine in 1869 pointed out that mixing sand with seeds and selling paste imitations was prevalent and had not been made illegal. So it was not until proven scientific tests were available, and proper legislation was passed in 1920 that the poor gardener could sow seeds he or she had purchased with some confidence that they would germinate and develop into the vegetables they were advertised to be.